Area of Gaussian

Shoutout Hasham, the bomb!

A super common function is the Gaussian distribution, or bell curve. It appears in machine learning and almost everywhere in statistics, and has some really cool properties. As a probability distribution, it is normalized to have a total area of 1, but the unnormalized version has a surprising area. The guassian function is defined as:

\[e^{-x^2}\]We’ll look at the total area $A$, where

\[A = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2} dx\]What’s really interesting about this, is that there’s no way to solve for the integral using normal everyday elementary functions. Instead, we have to pull out some crazy tricks.

Trick 1 is to try to evaluate $A^2$ instead, but changing the integration variable in one of the integrals. You can do this because the integral still represents the same area regardless of what variable you use.

\[A^2 = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2}dx \times \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-y^2}dy\]Now we can combine these integrals together since they are independent of each other:

\[A^2 = \int \int e^{-(x^2 + y^2)}dx \ dy\]Trick 2 is to switch to polar coordinates now! This is the motivation behind considering $A^2$ and using $x$ and $y$: now we can smooth switch into polar coordinates, which gives us definite bounds for one of the integrals.

When switching to polar, we consider $r$, the magnitude of our point, and $\theta$, the angle our point makes from the positive $x$ axis. Pythagorean theorem tells us $r^2 = x^2+y^2$, and when switching our coordinates of integration, we have that $dxdy = dA = rdrd\theta$. An explanation of why is at the bottom of this blog post. Applying this, we integrate a full rotation, with $r$ stretching from 0 to infinity.

\[A^2 = \int_{0}^{2\pi} \int_{0}^{\infty} e^{-r^2}r dr d\theta\]Because our function is completely independent of theta, we can switch the order of integration:

\[A^2 = \int_{0}^{\infty} \int_{0}^{2\pi} e^{-r^2}r d\theta dr = \int_{0}^{\infty} \left( e^{-r^2}r \theta \Big|_0^{2\pi} \right) dr = \int_{0}^{\infty} \left( e^{-r^2}r 2\pi - e^{-r^2}r0 \right) dr = \int_{0}^{\infty} e^{-r^2}r 2\pi dr = 2\pi \int_{0}^{\infty} e^{-r^2}r dr\]Perfect, now we’ve evaluated one of the integrals, and what we have left looks similar to what we started with, but with an extra factor of $r$, which makes all the difference, because now we can use U-sub to solve the integral.

\[u = -r^2, du = -2r dr\] \[\implies A^2 = 2\pi \int_{0}^{-\infty} e^u du \times \frac{1}{-2} = -\pi \int_{0}^{-\infty} e^u du\] \[\implies A^2 = -\pi e^u \Big|_0^{-\infty} = -\pi(e^{-\infty} - e^0) = -\pi (0-1) = -(-\pi) = \pi\] \[\boxed{A = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-x^2} dx = \sqrt{\pi}}\]Once again crazy! We have a well-known function, which proves tough to integrate, but when you pull some crazy tricks, reveals a reference to $\pi$, which seemingly would have nothing to do with this! It’s funny how the randomest numbers appear in the wild, like $e$ in the probability of dearrangements, and $\pi$ in the area of this gaussian function.

Thank you Raghav my Math & CS goat for originally showing me this one day in CS173 Office Hours when we didn’t have any students! I think he learned it from insta reels lmao.

\[\square\]Appendix

I said I’d show why $dA = rdrd\theta$ so here goes:

This is a slightly hand-wavy explanation, because I don’t understand what exterior algebra is, but if you want the full mathematical reasoning, look here: link

I’d also like to mention I’m not lame and didn’t just copy this down, I came up with this then looked through the post.

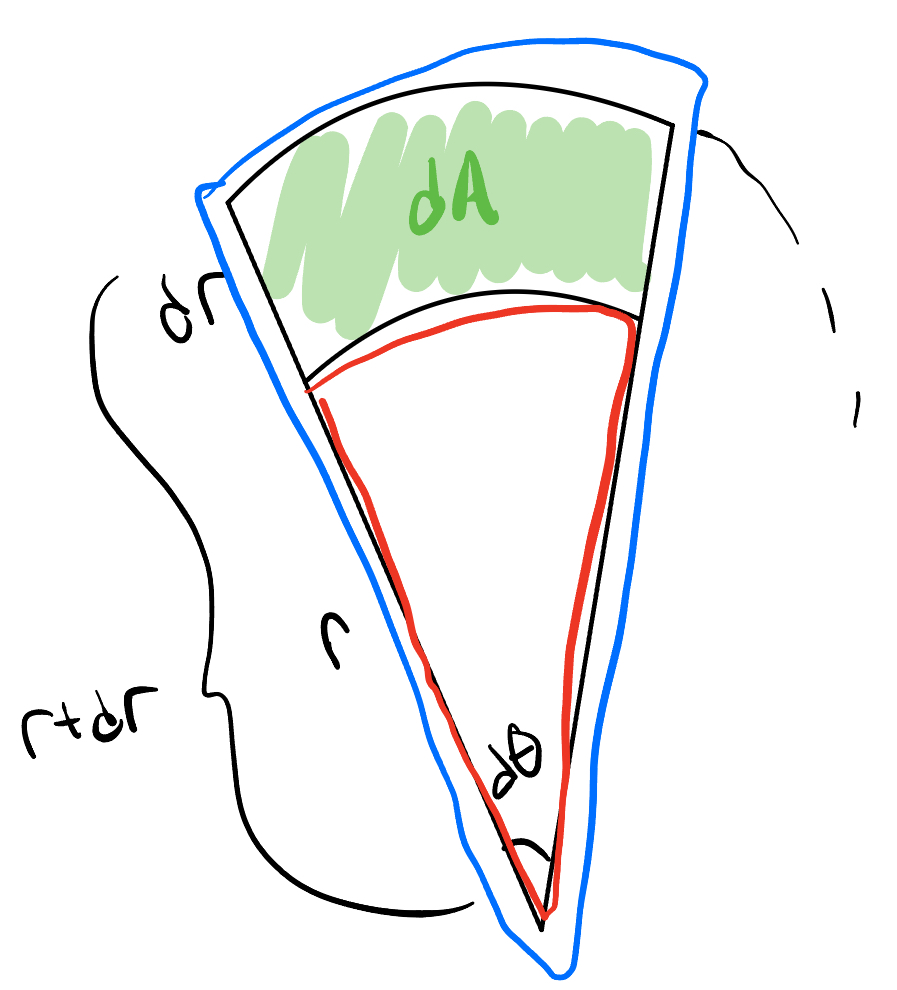

So we want to look at an area created from a tiny polar rotation with a tiny change in radius. Here we can see exactly that, with the green area our infinitesimally small $dA$. In order to find this area in terms of our polar variables, we refer back to the same idea behind finding arc-length. Find the total area as if it were a circle, then take the fraction that we are looking at. In our diagram we do this twice, once to find the blue section, and once for the red section (the only difference is their radii). Subtracting them will then give us $dA$.

The blue section has a radius of $r+dr$. So the area of the circle is $\pi (r+dr)^2$, and the fraction we want is $\frac{d\theta}{2\pi}$. Applying this to the red section as well, we get

\[dA = \frac{d\theta}{2\pi}\pi(r+dr)^2 - \frac{d\theta}{2\pi}\pi r^2 = \frac{d\theta \pi}{2\pi}((r+dr)^2 - r^2) = \frac{d\theta}{2}(r^2 + 2rdr + dr^2 - r^2) = \frac{d\theta}{2}(2rdr + dr^2)\]Now this is the iffy part, since $dr$ is already infinitesimally small, $dr^2$ is negligably small (and according to the link above, “symmetric”?), so we can ignore it. Then we get

\[\boxed{dA = \frac{d\theta}{2} \cdot 2 r dr = rdrd\theta}\]